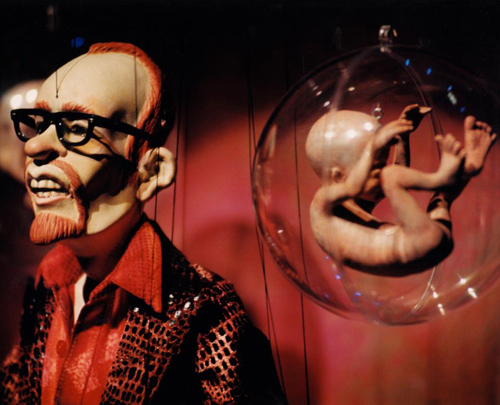

On a stage divided into three miniature playing areas, with Burkett hovering in full view above, he tells the story of Edna Rural, a “good woman” from the prairies who does her duty both in church and in the home, by raising — and painfully accepting — a son, Eden, who turns out to be homosexual, burying a husband who contracted AIDS from tainted blood and finally acknowledging out loud her own status as HIV positive.

Meanwhile, her son — who is adopted — has vented his rage against a repressive childhood (the scene in which his father beats him for wearing his mother’s wedding dress is terrible and real) by becoming a terrorist. And the search for his birth mother leads him to an old-time movie star he fantasized about during his unhappy childhood; the problem is, she turns out to be a vampire.

The contrast between Edna’s simple country life and the gothic humor and horror of the creatures of the night weaves seamlessly through the play and the climax — an eventual battle for supremacy between the vampire and Christ, the latter played by Burkett from above — is a moving metaphor for the struggle of good over evil.

In one memorable scene, Burkett comes down off his perch and sits on the stage, with the vampire at his throat. At the last moment, as she is about to suck his blood, he reaches down for a crucifix and stabs her through the heart. His symbol of agony has become her deliverance. And Eden, though he dies from the earlier wounds inflicted by the vampire, is off to heaven.

Burkett is clearly testing his rage at the global AIDS curse and at his own childhood on the prairies. As he (Christ), Eden and Edna lock in verbal combat, with tiny Edna, head tilted up, shaking her wooden fists at the savior who has appeared to her as a face in a quilt she is making, Burkett’s anger at a God who appears to have deserted his children is searing.

Yet there is also laughter, life and fun in “Street of Blood,” much of it provided by Burkett’s caustic but always warmhearted wit. And there are songs and music as well. All of it, with the exception of some pre-recorded sound, is created live onstage.

On one level, it is impossible not to be awed by the dexterity and talent of the master puppeteer, as he works the strings from above with only the help of a stage manager to put things in position; on another level, there are huge stretches of the show where the characters are so alive, so convincing, that they seem to be acting on their own.

Variety

Mira Friedlander

JANUARY 2, 2000